(Week 6 of 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks).

Week 6 of breaking down my writer’s block with a year-long family history challenge. This post is very late, as I’ve returned to work full-time and even though I started this three weeks ago, I’ve been having trouble finishing it. Welcome to my sixth post of 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks where I decided to share my Ukrainian immigrant ancestor before having any idea what would happen this week.

February Theme: Branching Out / Week 6: Maps

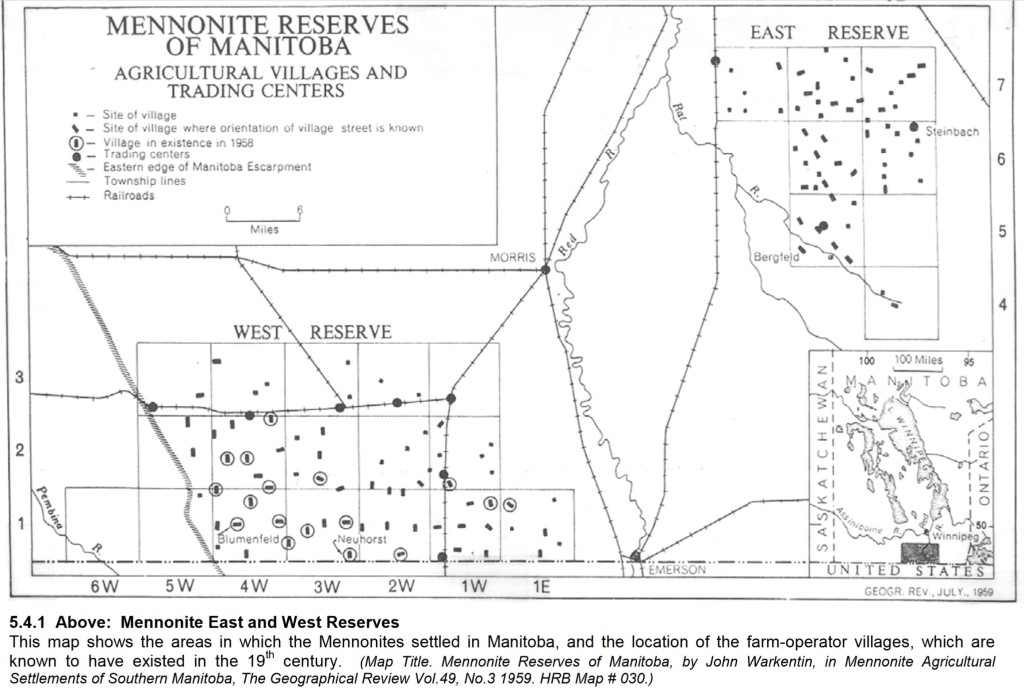

My immediate family is prone to a keen sense of wanderlust which I’ve always ascribed to my paternal grandfather. Klaas was his father, and my most recent immigrant ancestor. He arrived in Canada in 1875 from the Crimean peninsula at the age of 19 with his twice-widowed mother and younger siblings, landing in Quebec via Scotland before travelling again to the East River Mennonite reserve outside of Winnipeg.

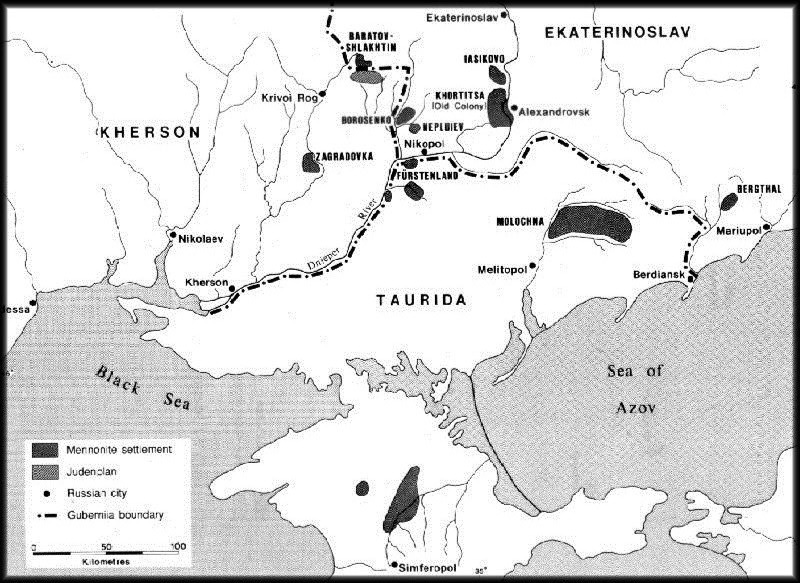

The farming community that he and his family left behind was itself a colonial outpost from a settlement in Prussia going back to the 1600s. Before that, their ancestors had mostly lived in Holland. In the late 1700s, Catherine the Great coaxed a colony of Mennonites from her Prussian homeland into Ukraine by offering them land grants in exchange for respecting their pacifism (as in, she promised they would not have to fight in the Russian army). The Bergthaler Colony that Klaas was born into was a daughter colony of the two original Ukraine colonies. By the time he reached adulthood, the political tides of Europe had shifted again and the Mennonites of both colonies began looking to the Americas (North and South) for land to farm. The instincts to move rang true, as within two generations any Mennonites left in Ukraine had been wiped out—first by the Red and White army clashes and later by Stalin.

To be honest, Klaas Peters does not seem to have been very well liked. He is described as self-interested and authoritarian. Citizens of the town he built burnt him in effigy after WWI (due to a mix of anti-German sentiment coupled with debate of the legitimacy of his pacifism as he was no longer a member of the Mennonite Church at that point). His treatment of his own family seems to reflect the same qualities. The biography of Klaas Peters in the second half of his book The Bergthaler Mennonites, written as an addendum by Leonard Doell, describes an autocratic man who left his pregnant wife and young children to fend for themselves in a sod hut while he travelled the world as an immigration agent for the fledgling Canadian government. Later, on deciding he and his family should leave Manitoba to settle in Alberta, he pulled his sixteen year old son out of school and sent him to raise cattle on a bare plot of land he’d purchased there. Two years later, Klaas pulled the same son off the ranch and told him he was to be the butcher in a shop he’d built in town. My grandfather, the youngest of Klaas’s several sons, had enough of his father by the age of fourteen and ran away to live with a brother. When Klaas died, none of his children bothered buying a gravestone.

Back to young Klaas on the Eastern Reserve of Manitoba—he didn’t stay for long, shifting over to the West reserve and the tiny farming town of Gretna where he met and married his wife Katarina Loewen, also a Mennonite from the Ukraine. They had ten children altogether, including my grandfather, though not all lived to adulthood.

Klaas, seeking the greener grass, uprooted the family soon after to yet another newer Mennonite settlement in Didsbury Alberta, halfway between Calgary and Red Deer. I found a photo of Didsbury in 1905, looking spectacular. The entire main street with its wooden buildings burnt down in 1914, including the butcher shop. But by then, Klaas had moved on to Waldek, Saskatchewan and another (failed) attempt at becoming a town founder.

He settled with his wife in Waldek to teach. He built a tavern. My grandfather and his brothers played in a brass band together. One of the brothers, Jacob, actually moved to California and played on the vaudeville circuit before tragically contracting Tuberculosis and coming back home to die. (When we cleaned out my grandparents’ house after my grandfather died, I came across a trumpet, still in its case. I was very sorry that I never knew he played.) If this tavern-owning and brass-playing does not sound very Mennonite-like, that is correct—Klaas and family had left the Mennonite Church for the Swedenborgian Church, similar in many ways but less strict.

Near the end of his life, Klaas moved once more, relocating to Florida with his wife where he wrote and published his book about the resettlement of his Bergthaler Colony to the Manitoba prairies. In Florida, he survived a bout of Spanish flu. After a short time in Florida, Klaas and Katrina returned to Canada to live out their last few years. Klaas left behind a complicated legacy as a “folk historian,” an orator, a pacifist, a book salesman, a teacher, a reverend, a land agent, a town founder and, apparently, a bit of a jerk—but a legacy nonetheless.